I didn’t pay my rent on time. It was my mistake. So if my landlord tells me to move out, I have no choice but to leave straight away.

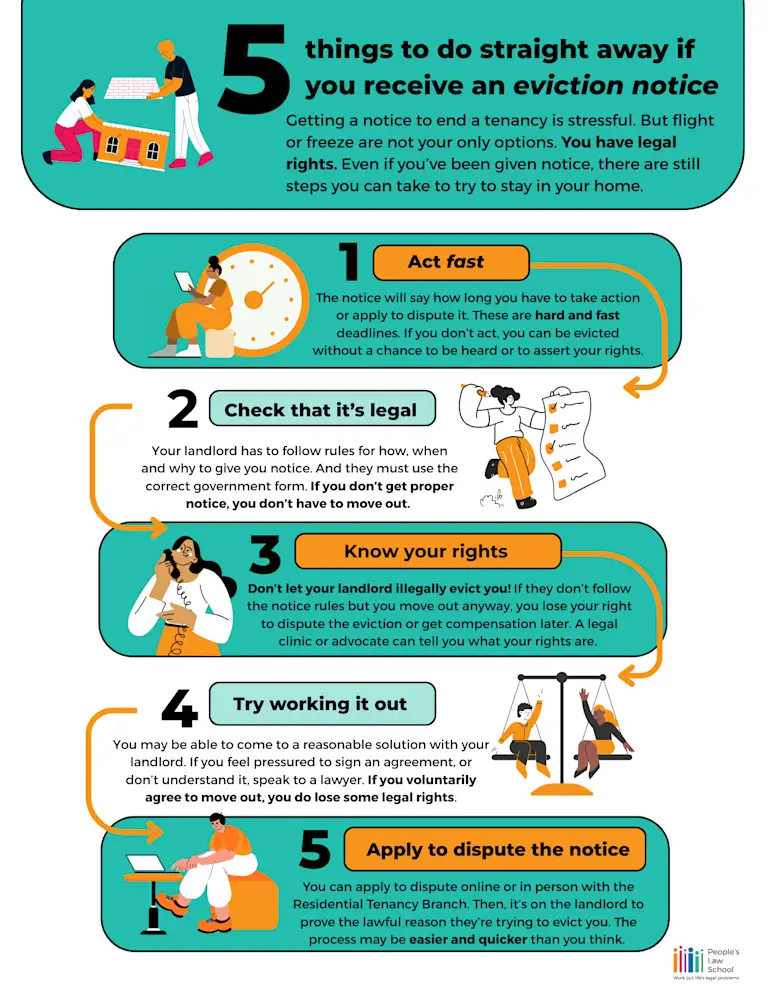

As a tenant, being told to vacate your home is stressful. But it doesn’t always mean you have to pack your things and go. Your landlord has to follow the law. There are steps you can take to try to work out the issue with them. And if you think your landlord is being unfair, you have options to get help and stay in your home.

What you should know

“We were so grounded in our community — things like weekly bingo, cultural events and child care at our local friendship centre. My mom lives with us and we’d asked the landlord to make the bathroom more accessible for her. Two weeks later, they sent an email saying we had to go. There were no forms attached. But their email sounded official, so we left.

Having to deal with any legal process — I usually try to stay away from those things. And fighting the eviction would have added to our stress. But being evicted has been totally devastating. I wish I had taken a deep breath and stood up to the landlord. What they did was just not right."

– Gus, Nanaimo, BC

If your landlord sends you a text telling you to vacate your home, this is not a legal eviction. Same thing if they tell you in person. These are not legal ways for a landlord to give notice of an eviction. Nor is email, unless you provided an email address for the landlord to serve documents to and they use the proper eviction form.

If you don’t get proper notice, you don’t have to move out.

Using this checklist, make sure that your landlord is playing by the rules. For the notice to be legal (and enforceable), it must:

Be in the correct form. The form should have one of these numbers in the top right-hand corner: RTB-29, RTB-30, RTB-31, RTB-32L, RTB-32P, or RTB-33.

Tell you the date the landlord wants you to move out by. On the form it’s called the “effective date.”

Be completed, signed, and dated.

State a reason for ending the tenancy that’s allowed under the law (see below, under there must be a legal reason).

Be given to you by mail, by handing it to you in person, or by attaching it to the door of the rental suite. The form can be attached to an email, but only if you have previously provided an email for service (such as in the tenancy agreement or on a separate form). Sliding an eviction form under the door or texting it are not legally valid ways to serve notice.

Even if you’re served a proper eviction notice, you don’t have to go just yet. An eviction notice is not an order to leave that same day. The notice should say the date you must move out by (the “effective date”). It can’t be any earlier than the minimum notice period. This notice period varies depending on the reason given. The minimum notice period will be up top of the notice. Sometimes it’s very short.

Pay attention to the way you were given notice, too. That will determine when you’re taken to have received the notice — that is, when the clock starts ticking for you to take action, apply for dispute resolution, or move out. For example, say your landlord emails you an eviction notice on September 1. The law considers you received that notice on the third day after it was sent, that is, September 4.

Your landlord can’t physically remove you

Your landlord cannot force you to move out as soon as they’ve given you notice. Even if the notice period has expired, they have to follow a legal process to have you removed from the unit or to change the locks. And they can’t do this themselves. Only a court-ordered bailiff can do those things, and only if the landlord has a writ of possession from the Supreme Court.

A different way to think about the eviction notice

No doubt, you should take an eviction notice seriously. But it may be helpful to think of the notice as a tool to engage with your landlord. In other words, the notice is alerting you to an issue that needs your attention. Depending on why you’ve been told to leave, you may be able to resolve the issue informally with your landlord. The end result could be that you get to stay housed.

Here’s an example. Some corporate landlords will automatically issue a 10-day notice of eviction if rent is late. Or they may issue a notice as a last-resort option to deal with an issue they’ve tried to flag with you before. It’s possible that they may see it as a hassle to go through the dispute resolution process or to find a new tenant. In other words, find out if they prefer to work with you to fix the issue than to follow through on the notice.

Let’s take a look at the late or unpaid rent scenario. Tell your landlord what happened. Especially if you’re dealing with a private landlord, you might have success striking a deal. For example, are there any useful skills you can offer in exchange for rent? (This could range from gardening to bookkeeping.) Are they open to a payment plan? Get any negotiated agreement in writing. And if you do manage to come up with the rent, get a receipt of full payment and ask the landlord to cancel the notice.

If you receive an eviction notice, there are hard and fast deadlines that you must meet to avoid getting evicted. So pay careful attention to them. The eviction notice will say how long you have to dispute it. The deadline is clearly stated at the top of the first page.

If you don’t take action or dispute the notice in time, your landlord can legally assume that you’ve agreed to end your tenancy. That means you have to move out on the effective date. If you refuse to leave, your landlord can apply for an order of possession without a participatory hearing. That’s a hearing where you both get to tell your side of the story and share evidence.

For example, if you’re late on rent, there’s a very short window of time between when you’re given notice to vacate and when your landlord can evict you. If a tenant is late on rent, most landlords will automatically issue a 10-day notice to end the tenancy. The law says you only have five days to pay the rent or dispute the notice. If you don’t do either of these within five days, the tenancy is over. You’ll have to move out by the effective date on the notice. Otherwise, the landlord can take legal steps to force you out.

It’s always open to you to ask your landlord for a grace period beyond these strict timelines. But legally speaking, there’s not much room for delays or mistakes on your end. In exceptional circumstances, the Residential Tenancy Branch can extend the deadline.

A landlord can’t evict you just because you’ve had a falling out or because they want more rent. They must give you a valid reason that’s recognized under the law. There are five main reasons that landlords are allowed to give for ending a tenancy:

Unpaid rent. If you don’t pay your rent on time, or if you don’t pay in full, the landlord can give you a 10-day eviction notice. (If you haven’t paid your utilities in time, the landlord can give you a written demand to pay. If you don’t pay up within 30 days, the landlord can give you a 10-day eviction notice.)

The tenant broke certain rules. A landlord can give you a one-month eviction notice "for cause." The law sets out the specific situations where a landlord can end a tenancy because of something the tenant did, or didn’t do.

The landlord or their close family are moving in. If the landlord plans to use the rental property for themselves or a close family member, they can give you a three-month eviction notice. A close family member is a spouse, parent, or child of the landlord (or child of their spouse). The landlord must honestly intend to follow through on these plans.

A new purchaser or their close family are moving in. This may happen if the landlord sells the rental unit. The new purchaser may decide they want to take over the rental unit for themselves. The landlord can give you a three-month notice on behalf of the purchaser.

The landlord plans to do major renovations. In this case, the landlord must ask the Residential Tenancy Branch for permission to evict you. They can’t simply give you an eviction notice. The notice period is four months.

The government of BC further explains the types of evictions that are allowed in BC.

Just saying the word “eviction” doesn’t give your landlord the right to kick you out of your home. There’s a legal process they have to follow that we’ve outlined above. An illegal eviction happens when a landlord ends the tenancy outside of this process. Here’s the catch: if your landlord does this and you decide to move out anyway, you lose your right to dispute the eviction or get compensation later on. (Your landlord, on the other hand, loses nothing.)

Watch for these common ways that landlords try to illegally force tenants out:

Telling you to leave verbally or by text. In other words, not giving you proper notice. There are specific forms that landlords must use if they want to evict you.

Giving a bogus reason for eviction. Under the law, there are specific reasons that a landlord can give to evict a tenant.

Acting dishonestly. If you suspect that your landlord may be acting in bad faith, ask more questions. Make a record of their answers and your observations.

Refusing to maintain the rental unit. A landlord may do this with the hope that it becomes so unpleasant that their tenant leaves.

Retaliation for complaints. This is where a landlord threatens to evict you shortly after you’ve made a complaint.

Harassment. A landlord may use threats or intimidation to bank on your choosing to walk away rather than deal with friction. This bad behaviour is not allowed. Here are some steps you can take if your landlord is harassing you.

Forcing or pressuring you to sign a mutual agreement to end tenancy. Watch out for a landlord who tries to pressure you to sign an agreement to end the tenancy, instead of issuing a notice. You do not have to sign this type of agreement if it’s not in your interests. Voluntarily leaving without getting proper notice means you lose the right to dispute the eviction and get compensation (such as for bad faith evictions) later.

Discrimination. Your landlord can’t evict you based on a protected characteristic, such as a disability, your race, or your religion.

In these kinds of situations, your landlord is breaking the law. If you have not been given a notice to end the tenancy, you do not have to leave your rental unit. If your landlord is acting improperly, reach out for help. More on this below, under deal with an eviction.

If efforts to resolve the issue informally with your landlord fail, you can dispute an eviction notice. You do this by applying for dispute resolution. This is the official process to resolve problems between landlords and tenants in BC. If you don't accept the eviction, it’s usually a good idea to dispute the notice because:

If you don’t dispute it in time, the landlord may assume you accept the eviction. If you don’t move out by the given date, the landlord can apply for an order of possession without a participatory hearing. That means you lose your chance to tell your side of the story and give evidence.

You can’t be forced to move out while there’s a dispute resolution application that is outstanding. So applying for dispute resolution buys you some to find a new home if the eviction is upheld.

By applying for dispute resolution, you force the landlord to prove the reason they wish to end the tenancy. They must show that it’s more likely than not that the facts occurred as they claim.

Dispute resolution might sound intimidating and complicated, but you may be surprised how accessible it is. You and the landlord each explain your side of the story to a person, called an arbitrator. They decide what each of you should do about the problem.

The process is meant to be used by regular people without the help of a lawyer. While there are rules you need to follow, it’s much less formal than court. The hearing is usually held over the phone. It’s typically an hour long. If English is not your first language, you can request telephone translation for information about the process and the hearing itself.

Most people appear on their own. But you can get help at any stage of the process. You are allowed to have an advocate or lawyer help you. You may want to do this especially if you have a corporate or not-for-profit landlord. They’re typically able to bring more resources and experience to the table than you can. (See below on overcoming barriers to the dispute process.)

“I came home to an eviction notice posted on my door. They’re giving me four months ‘til they want me out. I’m a single mom — I don’t have spare time to take this on. I was freaking out. It turns out quite a few of my neighbours got eviction notices, too. We all got on a group chat. Nine of us wrote a letter to our corporate landlord, together, to complain about dodgy behaviour. Turns out the property manager had separate chats with each of us to try to increase rent above the legal limit. We’re going to fight this together. It definitely feels like there’s strength in numbers.”

– Sandy, Vancouver, BC

It’s normal to feel overwhelmed. Taking on a legal “fight” with your landlord might seem intimidating. But you can focus on getting help and services so that you stay housed.

Here are some ways you can set yourself up to successfully dispute an eviction:

Get legal help. A first step is reaching out to the Tenant Resource & Advisory Centre, an advocate or a legal clinic. These are all free options. The Everyone Legal Clinic is a low-cost fixed-fee option for legal help.

Get moral support. If you feel uncomfortable or scared talking to your landlord, you can bring a friend with you as emotional backup.

Talk to your neighbours. If the issue is happening to other tenants, you can approach the landlord together. Consider contacting a local tenants’ union to help you organize a co-ordinated response.

Communicate by text or email. Another option is to text or email your landlord instead of confronting them in person. (And it will create a record of your communications.)

Apply to waive the fee. The cost of applying for dispute resolution is $100. If you can’t afford the fee, you can request to have the fee waived when you apply. You’ll have to provide evidence of your income, such as an income assistance statement or recent bank statements.

Take care of logistics. If you need time to prepare for and attend a hearing, plan ahead to manage your schedule. You might need to arrange a babysitter. (Try looking for community services like one-off free childcare.) Arrange time off from work in advance or get someone to cover your shift.

Deal with an eviction

“Eviction” is often used to refer to any situation where a landlord has told you, or is otherwise pressuring you, to leave. But it’s important to understand where the eviction process actually starts.

Check that the eviction is for a legal reason

If your landlord is trying to illegally evict you, find out what your rights and options are. (See above, under what you should know.) As well, we have more detailed information if your landlord:

Check that the proper form has been used

If your landlord has given you some kind of notice, check that it’s in the approved government form. If it’s not, the notice period hasn’t started. The Tenant Resource & Advisory Centre has a template letter for when your landlord has given you an illegal eviction notice. If you decide to give this letter to your landlord, keep a copy for your records.

Check the timelines

If your landlord has given you proper notice, check the timelines:

First, use this calculator to figure out your window to apply for dispute resolution.

Second, look on the notice to confirm the day the landlord is telling you to move out by (the effective date).

Third, check whether they’ve calculated the effective date from the correct start date. The date you’re taken to have received notice depends on how the landlord gave it to you.

Set calendar reminders to keep you on task and stay on top of deadlines. In the meantime, you can take other steps to resolve the issue informally.

Dealing with the threat of eviction is stressful. It may even cause you to go into “flight” or “freeze” mode. If you’ve received notice, take a deep breath and try your best to gather your thoughts.

To make an informed decision, you should figure out what your legal rights are. The best way to do this is to connect with a legal advocate or a legal clinic. Many community legal clinics provide help with tenancy issues. Search online for a legal clinic in your area. As well, see below for other options for free legal help.

Once you have a solid understanding of the situation and your rights, focus on the outcome you want. Do you want to try to negotiate a deal with your landlord? Take informal action like organizing with neighbours? Dispute the eviction with the Residential Tenancy Branch?

It’s normal to want to avoid conflict. It can feel daunting and draining to fight the eviction with your landlord. And if you decide it’s too much trouble to take this on with your landlord, that’s your decision. Know that re-locating comes with its own stresses and inconveniences, too. Evicted tenants often face a steep rent hike and difficulty finding affordable housing in their area. And being pushed out of a neighbourhood usually means loss of community connections and services, longer commutes to work, moving schools and loss of social ties.

Reach out to those around you. This can help ease some of the overwhelm, both emotionally and logistically. If you live in a complex with other rental units, talk to your neighbours. They might be facing similar issues, and you could try to approach the landlord as a group.

As well, reach out to your friends and other networks of support. You might want to ask for financial support to help keep you afloat. Or for extra help around the house. Or childcare help so you can get your thoughts together in peace. Here’s a list of resources that includes non-lawyer community supports.

The prospect of losing your home can negatively impact your mental health. There are ways to find free or low-cost counselling services in BC.

You can use evidence to negotiate with your landlord or sway their thinking on the issue. You can also use evidence to prove your point of view, either to the landlord when having an informal chat with them or if you apply for dispute resolution with the Residential Tenancy Branch.

Here are some examples of evidence you can gather to support your position:

letters, emails, and text messages

the state of maintenance and repairs

the tenancy agreement

the condition inspection report

witnesses who can back up your story

receipts and invoices

photos, videos, or audio recordings

a journal documenting the date and times of any issues or communication

It’s especially important to record this type of information if you think your landlord is acting dishonestly. You may be able to use this evidence at a later time, such as if you want to get compensation for a bad faith eviction.

Depending on what the issue is, there are actions you can take to resolve the issue before ending up in dispute resolution.

Before you chat (or write) to your landlord, identify the reason that you’re being asked to leave. Have in mind a clear and thought-out argument for why you should be allowed to stay. The BC government has a helpful page on working out tenancy issues with your landlord.

For example, if you’ve received a 10-day notice for unpaid rent, try to find a way to make up the amount owing. This might look like asking friends or family, applying for a loan from one of BC’s Rent Banks, or applying for a crisis supplement through the BC government. If you pay within five days of getting a 10-day notice, your landlord cannot evict you. You may also consider writing to your landlord to request flexibility on rent payment; here’s a template letter you can use to get started.

In some situations, it may be appropriate to try solving the problem through mediation. A mediator is a neutral person who steps in to guide the parties toward a resolution. With mediation, disputes are resolved quickly, often as fast as a few weeks.

If you aren’t able to work out the issue directly with your landlord, you can apply for dispute resolution. An arbitrator with the Residential Tenancy Branch will hear and decide your case. If they agree with you, they can cancel the eviction notice so you don’t have to move.

Before applying, check that:

the landlord served you notice using the proper form, and

you’re within the timeline to dispute the notice.

You can apply online for dispute resolution. (You need a basic BCeID account to do so.) Click on the "start new application" button. The site will walk you through the application. The form will ask you whether you want to dispute a "notice to end your tenancy."

You also have the option to submit a paper application. Use this form if you are still living in the unit where the dispute is happening. You can submit the paper application in person at the Residential Tenancy Branch or any Service BC office.

Step-by-step guidance to apply for dispute resolution

Renting It Right is a free online resource for tenants in BC. It leads you through everything you need to prepare for and participate in a dispute resolution hearing with the Residential Tenancy Branch.

Common questions

It depends. If you live in transitional housing you’re not protected by the Residential Tenancy Act. That means your landlord doesn’t have to follow the eviction rules outlined above. This type of housing is temporary housing. It’s meant for folks who may be moving away from homelessness, an emergency shelter, a health or correctional facility, or from an unsafe housing situation.

On the other hand, tenants living in supportive housing are protected by BC tenancy law. This is long-term housing for people who need support services to live independently.

Be aware that a landlord may wrongly call something “transitional housing” when it is actually supportive housing. The Community Legal Assistance Society has more information on the difference between the two types of housing, and a Residential Tenancy Branch has a policy guideline on transitional and supportive housing.

The answer depends on what your tenancy agreement says. An occupant is anyone who lives in the rental unit who is not a tenant on the tenancy agreement. (This is different from a guest who is visiting temporarily. There are different laws about guests. The BC government lists some factors to consider to figure out whether a guest has turned into an occupant.)

Assuming your partner has moved in for good, read your tenancy agreement for any terms about occupants. If your tenancy agreement doesn’t limit the number of occupants allowed, note that your landlord can still give you an eviction notice if there are an “unreasonable” number of tenants in the rental unit. If you’re the only person living in your rental, it would be difficult for your landlord to argue that an extra person sharing the space (and bedroom) would be unreasonable.

On the other hand, if your tenancy agreement limits the number of occupants, then you have to comply with what you’ve agreed to. If you don’t, the landlord may have cause to evict you for failing to comply with a material term of the agreement.

As well, tenancy agreements sometimes allow additional occupants but require that you pay additional rent per additional occupant. (The law allows landlords to do this, unless the additional occupant is a child under 19.)

Whatever your tenancy agreement says, it’s a good idea to be honest with your landlord about your partner moving in. It may be in your (and your partner’s) interest to add them to the tenancy agreement as a tenant. This way, they’ll be protected by the Residential Tenancy Act.

If you receive a notice to end your tenancy, it must state the date you need to move out by. This is called the “effective date” of the notice. But if you apply to the Residential Tenancy Branch to dispute the notice, your landlord can’t evict you until your case has been heard and decided on. This is true even after the effective move out-date has passed.

Residential Tenancy Branch hearings are decided by arbitrators. When an arbitrator decides to uphold an eviction, they typically grant the landlord an order of possession requiring the tenant to move out on short notice. The default minimum timeline requires the tenant to move out within 48 hours of the tenant receiving the order.

An arbitrator can consider extending the order beyond the usual 48 hours. During the hearing, you can ask the arbitrator to give you enough time to move out in the event they decide against you. Some things you could bring to the arbitrator’s attention include:

circumstances that would make it hard for you to move on short notice, for example — having a disability, or being obliged to care for family members or pets

your solid rental-payment history to date, and your ability to pay rent going forward

your belief that the landlord could absorb a longer move-out deadline without too much hardship

Finally, you can’t be evicted unless the landlord follows the legal process to serve and enforce the order of possession. If you don’t move out, landlord can’t just change the locks on you or physically remove you.

If you live in a rental but are not on the tenancy agreement, your legal rights are more limited. Your roommate who is on the tenancy agreement wouldn't have to follow the eviction rules that landlords have to follow. They also don’t have to use the approved government forms or abide by the same notice periods under the Residential Tenancy Act.

That said, they can’t just tell you to leave and expect you to be out by the next day. They still have to give you a reasonable amount of notice to evict you. How much time? We explain that here.

You can’t be treated badly or unfairly because of a protected characteristic (which includes having a disability). This applies to all stages of a tenancy, including entering a tenancy agreement, the terms and conditions of your rental, and being evicted.

If you face a disadvantage due to your disability, your landlord may have a duty to accommodate you. They must take all reasonable steps to counter the disadvantage. For example, it may involve a landlord repairing a staircase to make it safe for a tenant who has a physical disability.

Sometimes, accommodation isn’t possible because it would cost too much. Or there may be negative consequences for others. To account for this, the duty to accommodate only extends to the point that it causes undue hardship.

Learn more about how you’re protected from discrimination in tenancy.

Who can help

Renting It Right

Free online learning platform teaches BC tenants how to find rental housing, maintain problem-free tenancies, and resolve legal disputes with landlords.

Tenant Resource & Advisory Centre (TRAC)

Help and advice for tenants experiencing legal problems.

Access Pro Bono Residential Tenancy Program

Free legal assistance and representation to low- and modest-income tenants.

Community Legal Assistance Society

For a member of a housing co-op facing eviction, or a renter facing eviction after an RTB decision, the Community Legal Assistance Society may be able to help.

BC Housing

Listings for emergency shelters, transition houses and subsidized housing available in the province. Click on “Housing Assistance,” then “Women Leaving Violence.”