Can I override a medical decision made for me by a temporary substitute decision-maker, if I subsequently become capable of making the decision myself?

If you’re not capable of giving informed consent to a health care treatment, someone will need to make the decision for you. If you don’t have another authority in place that addresses that specific health care need, a temporary substitute decision-maker may be appointed. This is someone who is temporarily appointed to make a specific health care decision for you. Learn more about this role.

What you should know

Generally, a health care provider can only treat you if they get your informed consent. You have the right to give or refuse consent to any medical treatment. For this rule to apply, you must be capable of making the decision.

Your consent must be informed. Your doctor or health care provider is legally obligated to explain your illness or condition to you, tell you about the proposed treatment, the risks and benefits of it, and any alternative treatments (including no treatment).

The law says that when a health care provider is figuring out whether you’re capable of giving consent, they must consider whether you can understand:

the information they’re legally obligated to explain to you, and

that the information applies to you.

The law says that a "near relative" can help you to understand (or demonstrate your understanding of) these matters.

In cases of emergency

If you’re unable to give consent, and there is a medical emergency, a health care provider may act without your consent. They may do so if the treatment is necessary to save your life or prevent serious harm, and a representative under a representation agreement isn’t available.

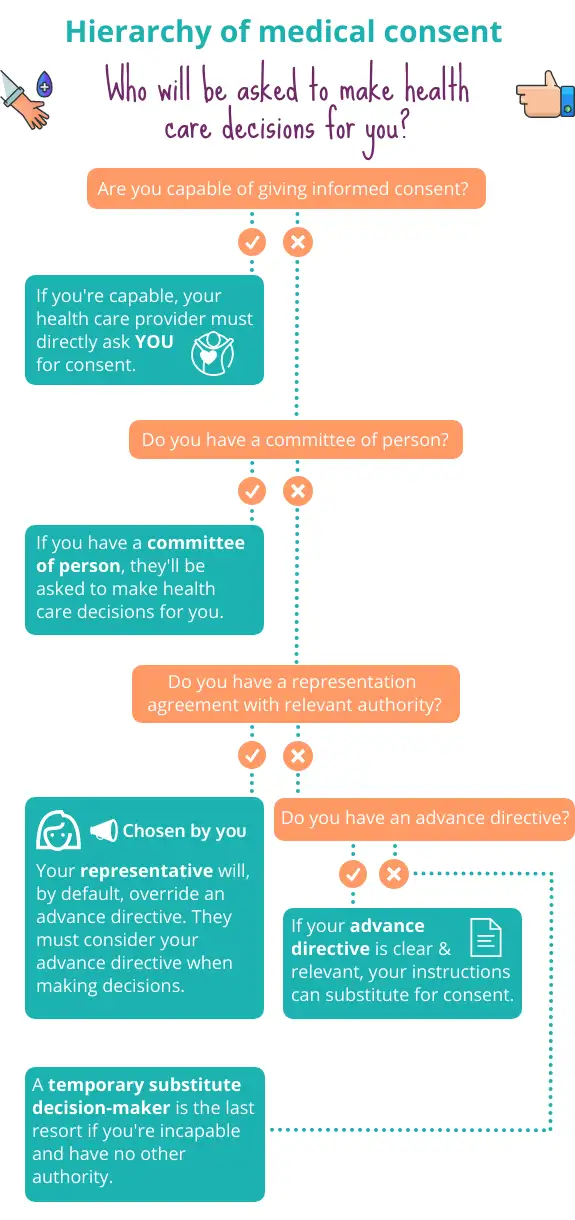

If you’re incapable of consenting to medical treatment, your health care provider will need to look elsewhere to get an answer. Under the law, there’s a hierarchy of authority that a health care provider must follow if a health care decision needs to be made and you’re not able to make it. The visual below steps through this decision-making hierarchy.

At the bottom of the hierarchy is a temporary substitute decision-maker. This person will be temporarily appointed to make a specific health care decision for you. They’ll only be called on if you don’t have another authority in place (such as a representative under a representation agreement) that addresses the specific health care need.

Learn more about representation agreements and advance directives, and how to prepare these documents.

“My husband Dave suddenly got ill. When the doctors tried speaking with him, he was groggy and incomprehensible. The hospital couldn’t get through to me so they reached out to our 20 year-old daughter. She gave consent to major surgery for her dad. It was an unexpected shift in our family dynamic, for sure.”

– Patrice, Richmond, BC

To appoint a temporary substitute decision-maker, your health care provider must make their way down a ranked list, until they find someone who’s available to make the decision for you. Someone lower down on the list can only be chosen if no one above them is available. The ranked list is set out under the law as follows:

Your spouse. This is someone you’re married to, or living in a common-law relationship with. There’s no minimum time period you need to have lived with someone to be considered a spouse.

An adult child.

A parent.

A sibling.

A grandparent.

A grandchild.

Another relative by birth or adoption.

A close friend.

Someone immediately related by marriage (including in-laws and step-children).

If there’s no one who can act from the above list, or there’s a disagreement about who should make the decision, then someone authorized by the Public Guardian and Trustee will be chosen. This person may be an employee of the Public Guardian and Trustee.

The chosen person must meet certain requirements

The person who’s chosen as your temporary substitute decision-maker must:

be at least 19 years old,

be legally capable of making the decision for you,

have no dispute with you,

have been in contact with you in the past 12 months, and

be willing to comply with their duties as a temporary substitute decision-maker.

As long as someone is over 19, age is irrelevant

As long as a decision-maker is over 19, age is irrelevant. Your oldest child won’t automatically be chosen over your youngest adult child. The same applies for other relatives, such as siblings.

A temporary substitute decision-maker has the temporary authority to give or refuse consent to health care treatment on your behalf. Their authority only applies to the specific health care decision at hand. Say another health care decision comes up that you’re not capable of making yourself. Your health care provider would need to return to the ranked list, and start the process again.

A temporary substitute decision-maker can make decisions about most kinds of health care. The law says there are certain kinds of health care they can’t consent to. For example, they can’t consent to controversial or irreversible treatments such as organ transplants or experimental surgery.

They can say no to life-saving treatment if you’re terminally ill or critically injured. However, they can only do so if there’s substantial agreement among the health care providers caring for you that the decision is medically appropriate and reflects your wishes or is in your best interests.

When making a decision on your behalf, a temporary substitute decision-maker must consult with you, if possible. They must also follow any wishes or instructions you expressed when you were capable. You may have verbally communicated these wishes or written them down.

If your wishes aren’t known, the decision-maker must give or refuse consent based on your best interests. This includes considering your current wishes, and known beliefs and values. It also includes considering the risks and benefits of the proposed health care.

“My brother Andre fell off a ladder while cleaning his gutters. At the hospital, they could see he had a brain injury. The hospital called our sister Jasmine. They wanted her to make some decisions. Jasmine and Andre have never been close. Now he’s in a coma and his doctors want to know whether to keep him on life support. He’s a vegetable. I know Andre would never have wanted to live this way. But Jasmine and me, we can’t agree. Someone said we might have to go to court. If the court doesn’t think either of us are a good fit, the Public Guardian and Trustee might be appointed.”

– Michael, Coquitlam, BC

If two equally ranked family members — for example, your siblings — disagree about a major medical decision, they may need to go to court. The court can appoint one of them as your committee of person. This is someone who’s charged with making health care and personal care decisions for an adult who can no longer do it for themselves. The court can also appoint anyone else they think is more appropriate.

Going to court is rarely a desirable plan A. It’s expensive and time-consuming and can cause unnecessary stress for family and others close to you. It can take months or even years for applications to be heard in court. This can delay access to money needed for your care and degrade your quality of life.

When the Public Guardian and Trustee might become involved

If there’s a disagreement about who should be chosen to make a decision, your health provider must choose a decision-maker authorized by the Public Guardian and Trustee. Contrast this with the situation where two equally ranked people (such as siblings) disagree about what should be done — this may have to be legally resolved by going to court.

Make your list

The list should include each person’s name, their relationship to you, and how to best contact them. Relevant details like “Johanna does night shifts and sleeps during the day” or “Max works as a teacher but can be called out of class for an emergency” will also be helpful.

Re-visit the requirements for temporary substitute decision-makers above. Make a note if someone who might be contacted doesn’t fit the criteria, such as “I’m estranged from my mother Maya Cruz.”

Everyone should do this. Even if you have a representation agreement, writing these details down acts as a back-up plan. For example, your representative might be out of the country, or otherwise unavailable.

If you’re asked for a point of contact

Upon admission to a hospital or care facility, you may be asked to name your spouse or a “near relative,” to be contacted as required. For example, they may be contacted if your condition changes. They may be asked to help you understand your medical options.

This is a different purpose than that of a temporary substitute decision-maker. If someone needs to be chosen as your temporary substitute decision-maker, it may or may not be that same “near relative.”

You can’t indicate preferences for certain people on your list. Your health care provider can’t just skip to someone at the bottom of the ranked list, and call them first. They must still work their way down the list, as set out by law (and described above, under what you should know). The point of writing down each person’s details is to save your health care provider valuable minutes, maybe even hours, when a medical decision needs to be made on your behalf.

When making a decision for you, a temporary substitute decision-maker is required, under the law, to follow any instructions or wishes you expressed while you were capable. They should also consider your known beliefs and values.

So it’s a good idea to share your wishes, values, and beliefs with anyone who could potentially make these decisions for you. This includes talking to family members and anyone who’s close to you. Doing so will give them the best chance to make decisions that align with what you would have wanted.

Think about every person in your life who could potentially be asked to be a temporary substitute decision-maker — would you ever want them to make a critical health care decision for you? If the answer is “no,” you should think about preparing other planning documents.

To get started, learn about your options for planning for your health care and personal care. If you’re ready to prepare legal documents, we can step you through preparing an enhanced representation agreement and an advance directive.

Common questions

Legally speaking, no one person has the automatic right to make decisions for you, not even your spouse. When providing you with health care treatment, doctors and other health care providers must follow a hierarchy of authorities. This means that they’re required by law to turn to certain people to get consent to health care treatment. If you don’t put the proper legal documentation in place, there’s no guarantee that your spouse will be the one who is chosen to speak for you when needed.

There are many advantages to choosing a representative rather than falling back on the default scheme under the law. The visual below sets out some of these advantages.

A temporary substitute decision-maker doesn’t have the authority to make personal care decisions. These include decisions about where you live, what and how you eat (such as whether you’d want to be spoon fed), who you spend time with, as well as personal safety. These kinds of decisions become particularly important if you develop a chronic illness or condition.

If a friend, family member, or doctor is concerned about any major health care decision made by a temporary substitute decision-maker, they can ask the health authority to review the decision. Each health authority in the province is required to have a dispute resolution process.

Under the law in BC, certain people can apply to court to challenge a decision by a temporary substitute decision-maker to give or refuse consent to health care. Those who can apply to court include a health care provider or the adult themselves (that is, the person who needed the medical treatment).

Under this same law, the court can be asked to say who the temporary substitute decision-maker should be.

Who can help

Nidus Personal Planning Resource Centre & Registry

Detailed information on personal planning, including template forms.