If I die without a will, my family gets to decide how to split my estate.

If someone dies without a will, they’re said to have died intestate. Those left behind may feel they have no guidance on what to do with the deceased’s property. But the law determines how it will get distributed, and who has the right to settle the estate.

What you should know

If someone in BC dies without a will, the law says how their estate will be divided. A person’s estate is made up of most of the property and belongings they own upon their death. (There are some exceptions, such as property held in joint tenancy.) The estate will be divided according to the mix of relatives left behind.

The first step is to determine whether the deceased had a spouse

“My grandparents never married. When Grandpa got sick, he had to move out of the house they’d shared for 40 years and into a care home. It was difficult for both of them. And there was never an intention to separate. They were in it for the long haul, even if they had to live apart. Grandpa died without a will. Even though they didn’t live together at the end, Nan was still considered to be his spouse under the law.”

– Justin, Victoria, BC

Under estates law in BC, people are considered spouses if they were:

married (and not separated) when the deceased passed away, or

in a “marriage-like relationship” for at least two years prior to death, unless one of them ended the relationship.

“Marriage-like relationships” include common-law unions. In these arrangements, the two people:

needn’t have been living together

must have been in a marriage-like relationship for two years (though not necessarily the two years immediately before the deceased’s death)

Sometimes, it’s not clear whether two people are spouses. If you’re not sure whether someone is the deceased’s spouse, or if you think the deceased might have been separated, it’s best to talk to a lawyer. It makes a big difference to how the estate should be distributed.

If the deceased had a spouse

“My husband Dave died without a will. We didn’t have any kids together. Dave had a daughter who passed away years ago. She had a son. Dave hadn’t seen his grandson since his daughter died, for complicated reasons. I wondered whether any of Dave’s money should go to his grandson. My lawyer told me that grandchildren get a share of the estate if their parent, who has died, was a child of the deceased. I got the first $150,000 of Dave’s estate, and then split the remainder with his grandson.”

– Nada, Surrey, BC

Under the law, when the deceased dies leaving a:

Spouse and no children. The entire estate goes to the spouse.

Spouse and children with that spouse. The spouse gets the first $300,000 of the estate and half of the remainder. The other half is divided equally among the children.

Spouse and children from a prior relationship. The spouse gets the first $150,000 of the estate and half of the remainder. The other half is divided equally among the children.

It’s possible to have more than one spouse under BC estates law. In this case, they split the spouse’s share equally (unless they agree or a court decides differently).

A spouse's right to the spousal home

If your spouse died without a will, the law says you have the right to acquire the spousal home. The deceased must have owned the home, and you must have ordinarily lived in it together. The home will be counted towards your share of the estate. In some circumstances, you may have to pay occupancy costs or even pay some money to the other heirs. It’s best to speak to a lawyer about your particular circumstances.

If the deceased didn’t have a spouse

If the deceased had no spouse, then the estate is divided among their children and sometimes their grandchildren or other descendants. A descendant means a surviving person of the generation nearest to the deceased.

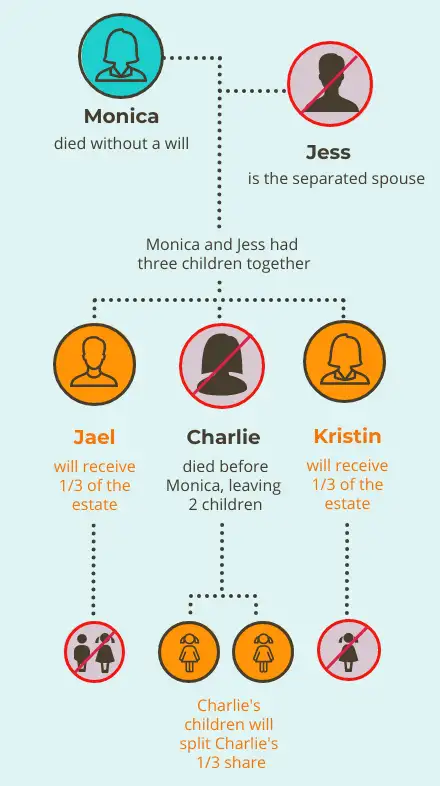

In the example below, Monica died without a will. Her separated spouse receives nothing. Two of her adult children are still alive, so they each get a one-third share. Monica’s daughter Charlie died before her, so Charlie’s kids split the remaining one-third of the estate.

If the deceased had no spouse and no descendants, then the estate goes to their parents. If their parents aren’t alive, it’s divided equally among their brothers and sisters.

There are other rules to figure out which next of kin may receive the estate if the deceased had no surviving spouse, descendants, parents, or siblings.

If the deceased has no next-of-kin, the estate goes to the provincial government.

While we're on the topic of wills

For most, making a will is a centrepiece of planning for their passing. Preparing a will can ensure those you leave behind are looked after, and that the things you own go to the people you want. We have step-by-step guidance on preparing a will.

When someone makes a will, they get to choose an executor. This is the person who manages their affairs after they die.

If someone dies without a will, the person who does this job is called the administrator. Someone usually has to apply to the court to get the legal authority to do so.

The people who can apply to administer the estate are listed under the law in order of priority. The spouse of the deceased is the first person who can apply, or they can nominate someone else to apply.

Applying for a grant of administration

Learn who can apply for a grant of administration and how to apply.

With a will, a person can appoint a guardian to look after any young children they leave behind after they die. Parents are usually guardians, but not always. Legal Aid BC explains who can be a guardian.

What if someone dies without appointing a guardian for their children under 19?

If there’s a surviving guardian, they’ll become the child's guardian. A surviving parent who isn’t the child’s guardian must apply to the court to become guardian.

If there’s no surviving guardian, the Public Guardian and Trustee will become the estate guardian. This means they’re responsible for managing the child’s money and legal affairs.

At the same time, the Ministry of Children & Family Development will become the child’s personal guardian. This is the person who has physical custody of the child and must care for them. The ministry remains guardian until someone else becomes the guardian. The new guardian may be appointed in a court order or have applied to adopt the child. In the meantime, the ministry may place the child in foster care or to live with a relative or friend. The court decides what arrangements are in the child's best interests.

The importance of naming a guardian in your will

Many people think that if both parents die, a family member will simply be able to step in and take care of young children. This is often the eventual result. But there are steps that must be taken to ensure that the right person is granted guardianship. The court’s opinion on who the right person is may differ from yours. Your best chance of ensuring that the right person (in your eyes) is chosen is to name a guardian in your will.

If someone dies without a will, a child under 19 might inherit a share of the estate. The law in BC says the minor’s share must be paid to the Public Guardian and Trustee of BC. This public body will hold the minor’s share in the estate until they’re 19. In the meantime, the child’s parent or guardian can apply to the Public Guardian and Trustee to release funds for basic expenses like food, clothing, and education. When the minor turns 19, they can demand all their money — no matter how much it is.

Another example of the importance of making a will

By preparing a will, a person can create a trust for any gifts left to minor children or others who might be under 19 when the will-maker dies. A trustee, chosen by the will-maker, can manage the minor’s share for the minor’s benefit until they turn 19 (or a later age if desired).

The law in BC says who’s responsible for arranging the funeral and paying the funeral expenses from the deceased’s estate.

If the deceased didn’t name an executor under a will, the job falls to the deceased’s spouse. If there’s no spouse or they’re not willing to step up, the law sets out a priority order for who to approach. Next in line are the deceased’s adult children, then adult grandchildren, a parent, and so on.

What if the right passes to people of equal rank (such as adult children)? The law says they can decide among themselves who should do it. If they can’t agree, priority descends in order of age.

Who can help

Public Guardian and Trustee

A government office that may agree to administer an estate when someone dies without a will.